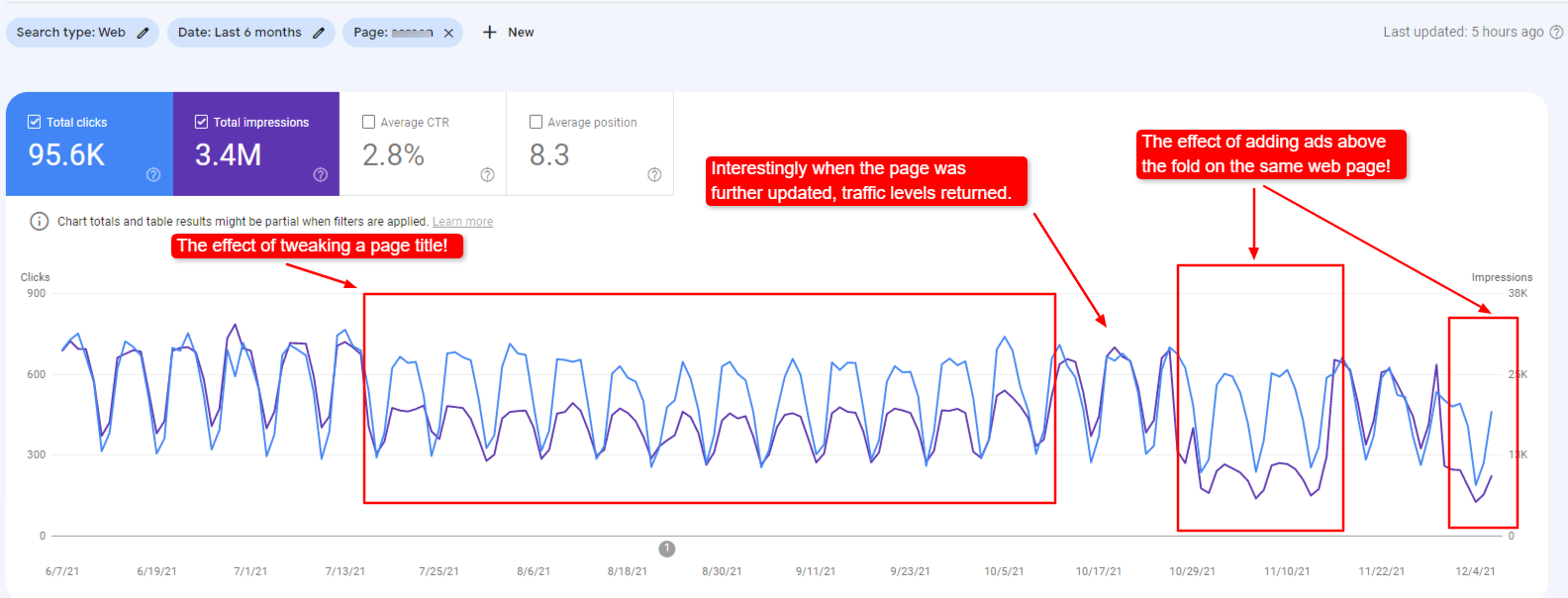

There’s a reason why Google says, “Don’t let ads harm your mobile page ranking“.

For more than two decades, we in the SEO profession have navigated the complex relationship between Google’s public mission and its commercial reality. The mission, to “organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful,” is a noble one.

The reality, however, is that Google is an advertising company. This creates an uncomfortable symbiosis, a fundamental conflict between serving the user with the best possible answer and monetising that user’s attention.

For years, our understanding of how Google manages this conflict has been based on a combination of public statements, tests, guideline analysis, and hard-won empirical observation. That era of inference is now over.

The landmark DOJ v. Google antitrust trial and the unprecedented leak of Google’s internal Content Warehouse API documentation have, for the first time, provided us with verifiable, evidence-based insights into the engineering that underpins this balancing act.

The trial, through sworn testimony, laid bare the immense internal pressures to meet revenue targets.

We heard from Google’s own executives about “shaking the cushions” to find ways to increase ad revenue, a pressure that exists in direct opposition to a purely user-first philosophy. Simultaneously, the trial confirmed the absolute primacy of user interaction data, captured by systems like Navboost, as one of the most critical inputs into the ranking algorithms.

clutterScore

Complementing the trial’s strategic revelations, the Content Warehouse leak provided the technical blueprint. It gave us the names of the attributes and modules that constitute the machinery of search, such as adsDensityInterstitialViolationStrength, violatesMobileInterstitialPolicy, and a previously unknown site-level signal explicitly designed to measure and penalise on-page clutter: clutterScore.

The long-standing debate about “user experience” has therefore been irrevocably transformed. It has shifted from a discussion about conceptual best practices to a concrete analysis of specific, measurable, and punitive signals within Google’s core systems.

This article will explore these new streams of evidence to answer a critical question for any publisher or SEO: what does Google really think about ads on a page, and how does it algorithmically account for their effect on ranking?

The important thing for you to know here is:

QUOTE: “Summary: The Low rating should be used for disruptive or highly distracting Ads and SC. Misleading Titles, Ads, or SC may also justify a Low rating. Use your judgment when evaluating pages. User expectations will differ based on the purpose of the page and cultural norms.” Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2017

… and that Google does not send free traffic to sites it rates as low quality.

QUOTE: “Important: The Low rating should be used if the page has Ads, SC, or other features that interrupt or distract from using the MC.” Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2019

From ‘Top Heavy’ to Mobile-First Penalties

QUOTE: “(Main CONTENT) is (or should be!) the reason the page exists.” Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2019

To understand where we are now, we must first revisit what Google has told us publicly. For over a decade, the cornerstone of Google’s official position on on-page advertising has been the “Page Layout Algorithm,” first announced in January 2012.

Known colloquially in the SEO community as the “Top Heavy” update, its stated purpose was to address a specific user complaint: landing on a page from search results only to be confronted by a wall of content above the fold (like Ads) instead of the content they were seeking.

In its original announcement, Google framed the issue squarely as a matter of user experience, stating, “We’ve heard complaints from users that if they click on a result and it’s difficult to find the actual content, they aren’t happy with the experience. Rather than scrolling down the page past a slew of ads, users want to see content right away”. The post went on to warn that sites dedicating “a large fraction of the site’s initial screen real estate to ads” may not rank as highly going forward.

This doctrine has remained remarkably consistent over the years, with subsequent refreshes of the algorithm in October 2012 and February 2014 reinforcing the same core message.

QUOTE: “So sites that don’t have much content “above-the-fold” can be affected by this change. If you click on a website and the part of the website you see first either doesn’t have a lot of visible content above-the-fold or dedicates a large fraction of the site’s initial screen real estate to ads, that’s not a very good user experience.” Google 2012

However, what has also remained consistent is a deliberate vagueness on the specifics. Google has never defined a precise ad-to-content ratio, a maximum number of ad units, or a pixel count that constitutes “too much.”

Instead, the language has always been subjective, referring to ads placed to a “normal degree” versus those that go “much further to load the top of the page with ads to an excessive degree”.

For years, many in the SEO community, myself included, have pointed to the inherent conflict in this advice, especially when Google’s own ad platforms would often recommend placements that seemed to contradict their search quality guidelines.

This focus on accessibility intensified with the web’s shift to mobile.

In 2017, Google officially began its transition to “mobile-first indexing,” meaning it “predominantly uses the mobile version of the content for indexing and ranking.” This shift was a direct response to user behaviour, as “the majority of users now access Google Search with a mobile device.”

With smaller screens, the negative impact of intrusive elements became even more pronounced, leading Google to introduce a specific penalty for intrusive interstitials on mobile in January 2017. As Google product manager Doantam Phan explained, pages that make content less accessible would be penalised, providing clear examples of violations:

“Showing a popup that covers the main content, either immediately after the user navigates to a page from the search results, or while they are looking through the page. Displaying a standalone interstitial that the user has to dismiss before accessing the main content. Using a layout where the above-the-fold portion of the page appears similar to a standalone interstitial, but the original content has been inlined underneath the fold.”

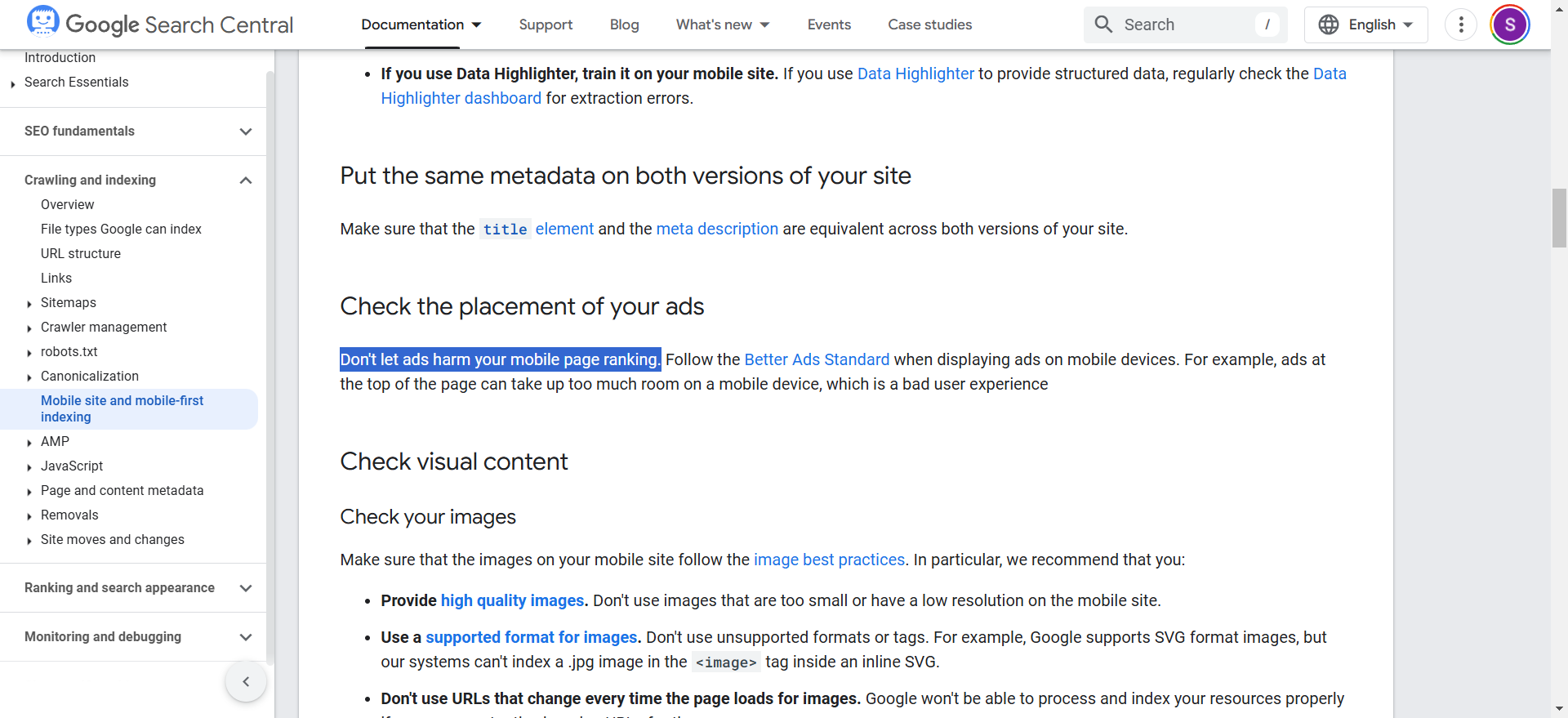

Google’s own documentation summarises the modern expectation perfectly: “Don’t let ads harm your mobile page ranking. Follow the Better Ads Standard when displaying ads on mobile devices. Make sure your mobile site contains the same content as your desktop site.” This is no longer just about ads at the top of the page; it’s about the entire mobile experience, from ad intrusiveness to content parity.

QUOTE: “Some things don’t change — users’ expectations, in particular. The popups of the early 2000s have reincarnated as modal windows, and are hated just as viscerally today as they were over a decade ago. Automatically playing audio is received just as negatively today. The following ad characteristics remained just as annoying for participants as they were in the early 2000s: Pops up – Slow loading time – Covers what you are trying to see – Moves content around – Occupies most of the page – Automatically plays sound.” Therese Fessenden, Nielsen Norman Group 2017

The Page Layout Algorithm, therefore, should be seen as the public tip of a much larger iceberg. It was the first official admission that page layout and monetisation choices have direct algorithmic consequences.

The recent leaks and trial testimony now reveal the sophisticated, modern machinery that lies beneath the surface – systems that have evolved far beyond this initial, relatively crude “Top Heavy” filter.

Defining ‘Annoying’ – The Better Ads Standards

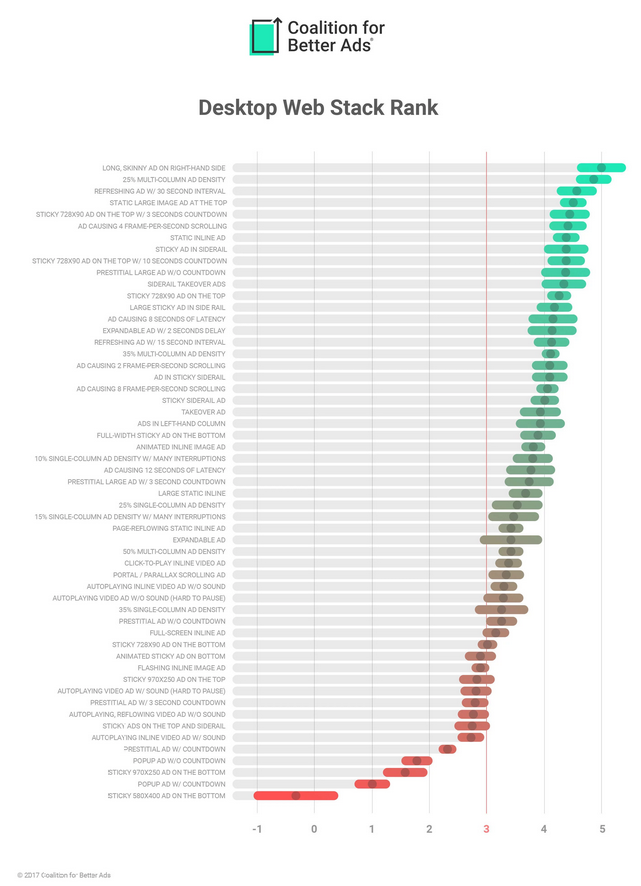

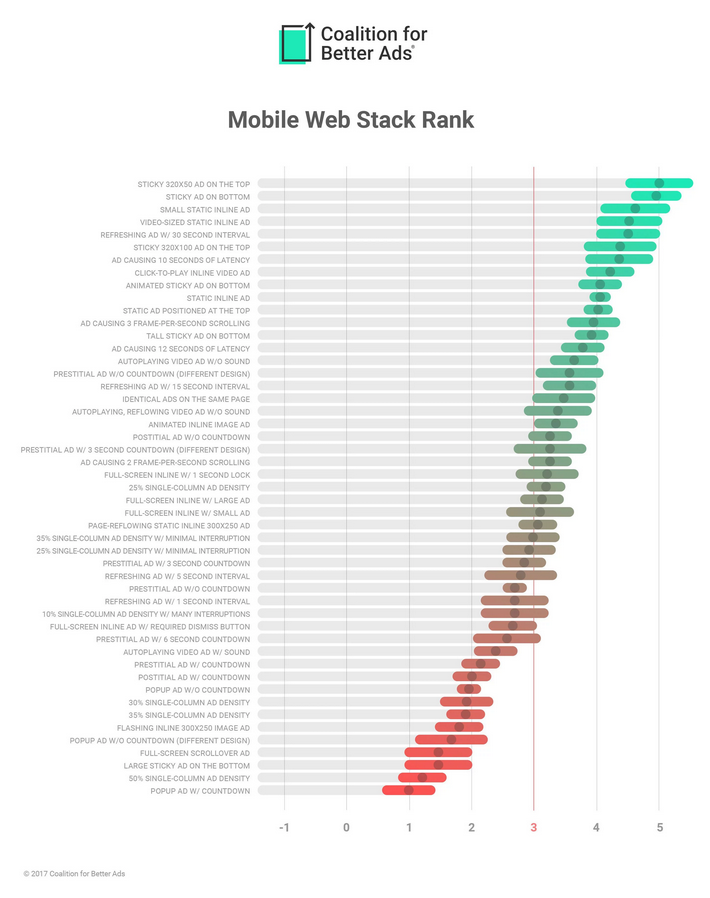

To move beyond the subjective nature of the original Page Layout Algorithm, Google embraced a more data-driven framework by joining the Coalition for Better Ads. This group conducted extensive research, surveying nearly 66,000 users to identify the ad experiences that are most likely to drive them to install ad blockers.

The result was the Better Ads Standards, a clear, evidence-based set of guidelines that define specific, unacceptable ad formats for both desktop and mobile web experiences.

Google’s publisher policies explicitly state that sites using its ad services “must not: place Google-served ads on screens that do not conform to the Better Ads Standards”. Google Search Essentials documentation clearly states in 2025, “Don’t let ads harm your mobile page ranking. Follow the Better Ads Standard”.

As Google’s Kelsey LeBeau noted in 2019:

“For years, the user experience has been tarnished by irritating and intrusive ads. Thanks to extensive research by the Coalition for Better Ads, we now know which ad formats and experiences users find the most annoying. Working from this data, the Coalition has developed the Better Ads Standards, offering publishers and advertisers a road map for the formats and ad experiences to avoid.”

The standards identify the following ad experiences as falling below the threshold of consumer acceptability:

Annoying Ads on Desktop

Pop Ups

Large Sticky Ads (ads that stick to the bottom of the page and take up more than 30% of the screen)

Prestitial Ads with Countdown (ads that appear before the page content has loaded)

Auto-playing Video Ads with Sound

Mobile Ad Layout Best Practices:

layout best practices for ads on mobile adhere to the same principles as desktop with a few others added in (which is very important):

Ad Density Higher Than 30%

Flashing Animated Ads

Full-screen Scrollover Ads

By adopting these standards, Google provided the industry with a concrete definition of what constitutes a “bad ad.” This is no longer about guesswork or interpreting vague phrases like “excessive degree.”

There is now a clear list of user-hostile formats, backed by large-scale user data, that are explicitly penalised. To help publishers comply, Google integrated the Ad Experience Report into Google Search Console, a tool that, according to Google’s guidelines, “is designed to identify ad experiences that violate the Better Ads Standards… If your site presents violations, the Ad Experience Report may identify the issues to fix.”

The Better Ads Standards represent a critical evolution, shifting the conversation from a subjective penalty to a clear, enforceable quality threshold.

Personal Observation: It is, however, an inconvenient truth for accessibility and usability aficionados to hear that pop-ups can be used successfully to vastly increase signup subscription conversions.

QUOTE: “While, as a whole, web usability has improved over these past several years, history repeats and designers make the same mistakes over and over again. Designers and marketers continuously need to walk a line between providing a good user experience and increasing advertising revenue. There is no “correct” answer or golden format for designers to use in order to flawlessly reach audiences; there will inevitably always be resistance to change and a desire for convention and predictability. That said, if, over the course of over ten years, users are still lamenting about the same problems, it’s time we start to take them seriously.” Therese Fessenden, Nielsen Norman Group 2017

Which type of adverts annoys visitors?

QUOTE: “When we review ad experiences, we make a determination based on an interpretation of the Better Ads Standards.” Google, 2021

Google states:

QUOTE: “The Ad Experience Report is designed to identify ad experiences that violate the Better Ads Standards, a set of ad experiences the industry has identified as being highly annoying to users. If your site presents violations, the Ad Experience Report may identify the issues to fix.” Google Webmaster Guidelines 2020

The Better Ads Standards people are focused on the following annoying ads:

Desktop Web Experiences

Mobile Web Experiences

Google says in the video about the Ad Experience report (which, I need to be honest, I have never seen a site flagged – ever – in Search Console for this infringement in over a decade) – but the advice reflects what we see in the leaked api documents:

QUOTE: “Fixing the problem depends on the issue you have. For example, if it’s a pop-up, you’ll need to remove all the pop-up ads from your site. But if the issue is high ad density on a page, you’ll need to reduce the number of ads. Once you fix the issues, you can submit your site for a re-review. We’ll look at a new sample of pages and may find ad experiences that were missed previously. We’ll email you when the results are in.” Google, 2017

Google offers some solutions to using pop-ups if you are interested

QUOTE: “In place of a pop-up try a full-screen inline ad. It offers the same amount of screen real estate as pop-ups without covering up any content. Fixing the problem depends on the issue you have for example if it’s a pop-up you’ll need to remove all the pop-up ads from your site but if the issue is high ad density on a page you’ll need to reduce the number of ads” Google, 2017

Your Website Will Receive A LOW RATING If It Has Annoying Or Distracting Ads or annoying Secondary Content (SC)

Google has long warned about web page advertisements and distractions on a web page that result in a poor user experience.

The following specific examples are taken from the Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines over the years.

6.3 Distracting/Disruptive/Misleading Titles, Ads, and Supplementary Content

QUOTE: “Some Low-quality pages have adequate MC (main content on the page) present, but it is difficult to use the MC due to disruptive, highly distracting, or misleading Ads/SC. Misleading titles can result in a very poor user experience when users click a link only to find that the page does not match their expectations.” Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2015

6.3.1 Ads or SC that disrupt the usage of MC

QUOTE: “We expect Ads and SC to be visible. However, some Ads, SC, or interstitial pages (i.e., pages displayed before or after the content you are expecting) make it difficult to use the MC. Pages with Ads, SC, or other features that distract from or interrupt the use of the MC should be given a Low rating.” Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2019

Google gave some examples:

- QUOTE: “‘Ads that actively float over the MC as you scroll down the page and are difficult to close. It can be very hard to use MC when it is actively covered by moving, difficult-to-close Ads.’

- QUOTE: “‘An interstitial page that redirects the user away from the MC without offering a path back to the MC.’

6.3.2 Prominent presence of distracting SC or Ads

Google said:

QUOTE: ““Users come to web pages to use the MC. Helpful SC and Ads can be part of a positive user experience, but distracting SC and Ads make it difficult for users to focus on and use the MC.

Some webpages are designed to encourage users to click on SC that is not helpful for the purpose of the page. This type of SC is often distracting or prominently placed in order to lure users to highly monetized pages.

Either porn SC or Ads containing porn on nonPorn pages can be very distracting or even upsetting to users. Please refresh the page a few times to see the range of Ads that appear, and use your knowledge of the locale and cultural sensitivities to make your rating. For example, an ad for a model in a revealing bikini is probably acceptable on a site that sells bathing suits. However, an extremely graphic porn ad may warrant a Low (or even Lowest) rating.” Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2017

6.3.3 Misleading Titles, Ads, or SC

Google said:

QUOTE: “It should be clear what parts of the page are MC, SC, and Ads. It should also be clear what will happen when users interact with content and links on the webpage. If users are misled into clicking on Ads or SC, or if clicks on Ads or SC leave users feeling surprised, tricked or confused, a Low rating is justified.

- At first glance, the Ads or SC appear to be MC. Some users may interact with Ads or SC, believing that the Ads or SC is the MC.Ads appear to be SC (links) where the user would expect that clicking the link will take them to another page within the same website, but actually take them to a different website. Some users may feel surprised or confused when clicking SC or links that go to a page on a completely different website.

- Ads or SC that entice users to click with shocking or exaggerated titles, images, and/or text. These can leave users feeling disappointed or annoyed when they click and see the actual and far less interesting content.

- Titles of pages or links/text in the SC that are misleading or exaggerated compared to the actual content of the page. This can result in a very poor user experience when users read the title or click a link only to find that the page does not match their expectations. “ Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2017

The important thing for you to know here is:

QUOTE: “Summary: The Low rating should be used for disruptive or highly distracting Ads and SC. Misleading Titles, Ads, or SC may also justify a Low rating. Use your judgment when evaluating pages. User expectations will differ based on the purpose of the page and cultural norms.” Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2017

… and that Google does not send free traffic to sites it rates as low quality.

QUOTE: “Important: The Low rating should be used if the page has Ads, SC, or other features that interrupt or distract from using the MC.” Google Search Quality Evaluator Guidelines 2019

Recommendation: Remove annoying ADS/SC/CTA from your site. Be extremely vigilant that your own CTA for your own business doesn’t get in the way of a user consuming the main content, either.

From my own experience over the last decade, your own CTA (Call-To-Action) on your own site might be treated much like Ads and SC are, and open to the same abuse and same punishments that Ads and SC are, depending on the page type.

The Human Filter – How Quality Raters Are Instructed to View Ads

The Human Bridge – How Raters Train the Machine to Hate Clutter

Between Google’s public-facing algorithms and its internal engineering lies a crucial bridge: a global team of thousands of human Search Quality Raters. For years, Google’s public line was that these raters’ evaluations were used to “benchmark the quality of our results” but did not directly influence rankings.

However, as I have covered in my analysis of the DOJ trial, sworn testimony has since confirmed a far more direct link: rater scores are a foundational training input for Google’s core AI ranking models, such as RankEmbedBERT. Understanding how these raters are instructed to evaluate pages is therefore essential to understanding the logic embedded within the algorithms themselves.

The Search Quality Rater Guidelines (SQRG), a comprehensive manual for these evaluators, dedicates dozens of pages to the concept of Page Quality (PQ). Raters are trained to assess a page’s purpose, its E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness), the reputation of the website and author, and the quality of the Main Content (MC), which Google defines as any part of the page that “directly helps the page achieve its purpose.” Critically, this evaluation is not limited to the core text of an article. It encompasses the entire user experience, with a specific focus on how advertising and Supplementary Content (SC) are presented.

The guidelines instruct raters to identify pages that are created with “little to no attempt to help users” and are instead designed primarily to make money. Ad-heavy layouts, distracting or deceptive ad placements, and aggressive interstitials are all cited as characteristics of low-quality pages. The guidelines are explicit:

“We expect Ads and SC to be visible. However, some Ads, SC, or interstitial pages (i.e., pages displayed before or after the content you are expecting) make it difficult to use the MC. Pages with Ads, SC, or other features that distract from or interrupt the use of the MC should be given a Low rating.“

The goal is to train the rater to see the page not as an SEO would – analysing headings and keyword density – but as a typical user would, reacting to a cluttered, spammy, or frustrating experience.

Perhaps the most telling piece of evidence within the guidelines is a direct and explicit instruction to the raters: “Do not use add-ons or extensions that block ads for Needs Met rating or Page Quality rating”.

This directive is not a minor footnote; it is a fundamental command that reveals Google’s intent. Google needs its human raters to see and experience the full, monetised version of a webpage. The ad load is not considered an extraneous element to be ignored; it is an integral part of the page’s quality, to be judged and rated.

This closes the loop between human evaluation and algorithmic enforcement. The process is logical and clear:

- A quality rater, with their ad blocker disabled, lands on a page heavily cluttered with auto-playing video ads, pop-ups, and large ad blocks that push the main content down the page.

- Following the SQRG, the rater assigns the page a very low PQ rating, flagging the distracting and unhelpful nature of the ad implementation.

- This page, with its specific DOM structure and resource load, now becomes a labelled, negative training example for Google’s machine learning systems.

- These systems learn to associate the architectural and content characteristics of this low-rated page with a poor user experience.

- The programmatic manifestation of this learned association is almost certainly signals like the

clutterScorefound in the Content Warehouse leak. The human rater’s subjective assessment of “clutter” provides the ground truth that trains an algorithm to identify and penalise it at the scale of the entire web.

Revelations Under Oath: The Publisher’s Dilemma

While the Quality Rater Guidelines show an organisation striving to define and reward a good user experience, the sworn testimony from the DOJ v. Google antitrust trial painted a much more complicated picture, one defined by the immense and constant pressure of revenue generation.

The trial revealed that Google is not a monolith with a single purpose but a complex entity with powerful, and at times competing, internal incentives.

The most stark evidence of this conflict came from testimony about the lengths the ads team would go to in order to meet quarterly revenue targets, including “shaking the cushions” to find new ways to hit their numbers.

This internal pressure creates a profound irony for publishers. We, too, are trying to make a living from our content, and for many, advertising via platforms like AdSense is the primary model. Yet, the very act of trying to increase our revenue by adding or optimising ad placements puts us at direct risk of being penalised by Google’s organic search quality systems.

For over a decade, I’ve seen the effects of this firsthand, advising clients on the negative impacts of ad clutter long before we had internal names for the penalties. Nobody wanted to hear it. The wall I always hit was the immediate fear of lost income: “that will decrease ad revenue”. I parted with customers over it.

I’ll never forget one who, after I recommended a less aggressive layout, asked me, “I know you want me to reduce my ads, but is there anything else?” The difficult truth was that while there were other issues, his site was a classic ‘disconnected entity’ with low contentEffort scores and a high commercial score – eg a lower quality affiliate site – the ad clutter was the most immediate, user-facing problem at the time.

This is the pincer movement publishers are caught in. On one side, Google’s business is driven by ad revenue. On the other, its Search division must protect the user experience to maintain market dominance.

This stands in direct contrast to the priorities of the Search team, as detailed in the testimony of Pandu Nayak, Google’s Vice President of Search. As I have covered previously, Nayak’s testimony confirmed the central role of user satisfaction systems like Navboost, which analyses trillions of clicks to determine which results best satisfy users.

The Search team’s primary incentive is to maintain and grow user trust, the very asset threatened by a poor, ad-cluttered experience.

Therefore, algorithmic features that penalise on-page clutter should be viewed not just as tools to help users, but as essential, automated defence mechanisms. They represent the Search quality team’s primary check and balance against the commercial incentives that degrade the core search product.

A signal like clutterScore is an internal control written in code, designed to protect the long-term viability of the user experience from the relentless pressure of short-term monetisation.

The Coded Consequence – Deconstructing the clutterScore

The Content Warehouse API leak moved the concept of an on-page ad penalty from the realm of algorithmic inference to documented fact. Buried within the nearly 2,600 modules and over 14,000 attributes was a specific feature that confirmed many long-held suspicions: clutterScore.

According to the documentation, clutterScore is defined as a “Delta site-level signal which looks for clutter on the site.” Its purpose is for “penalising sites with a large number of distracting/annoying resources”. While the leak does not provide an exhaustive list of what constitutes a “distracting/annoying resource,” the analysis suggests it includes elements like interstitials, video players, and excessive scripts—the very things that degrade page experience. Further technical detail notes that the attribute is part of a larger CompressedQualitySignals module and is an integer scaled by 100, implying it is a component within a broader suite of quality-related measurements.

This signal does not exist in a vacuum. The leak details a multi-faceted approach to identifying and demoting poor page experiences, with a particular focus on the mobile environment. A dedicated model, SmartphonePerDocData, is used for storing a suite of smartphone-related information, distinct from data collected for lower-end mobile devices. This model contains a granular set of attributes designed to evaluate and penalise specific mobile violations.

Within this model, we find attributes that go far beyond a simple pass/fail grade. The violatesMobileInterstitialPolicy is a straightforward boolean (true/false) attribute that demotes a page for violating the mobile interstitial policy. However, the leak also reveals a more nuanced counterpart: adsDensityInterstitialViolationStrength. This attribute provides a scaled integer from 0 to 1000, indicating not just if a page violates the mobile ads density policy, but the strength of that violation. This demonstrates a sophisticated, layered system that can apply penalties with surgical precision. This is complemented by other mobile-specific checks within the same model, such as isSmartphoneOptimized (a tri-state field indicating if a page is mobile-friendly), maximumFlashRatio (measuring the area of Flash on the page), and isErrorPage (flagging pages that serve an error to the smartphone crawler).

The most profound revelation in the definition of clutterScore, however, is its scope. It is explicitly described as a “site-level signal“. This is a critical distinction with significant strategic implications for publishers and SEOs. It indicates that Google is not merely evaluating ad clutter on a URL-by-URL basis. Instead, the system is designed to aggregate these assessments to form a holistic judgement about an entire domain’s approach to monetisation.

This aligns perfectly with other site-level concepts that have been confirmed through the DOJ trial and my own previous analysis, most notably the existence of Q*—a foundational, site-wide quality score that acts as a powerful ranking gatekeeper.

The site-level nature of clutterScore suggests a process where Google’s crawlers might analyse a representative sample of pages across a domain, assess their individual clutter characteristics, and then calculate an aggregated score that is applied to the site as a whole.

This elevates the stakes considerably. It is no longer sufficient to ensure that only your most important commercial or informational pages are clean and user-friendly. A pattern of aggressive monetisation and clutter on less-trafficked parts of a site – such as an old, neglected blog section or an archived forum – could contribute to a negative site-level signal.

This clutterScore could then suppress the ranking potential of the entire domain, including the high-quality pages you have worked diligently to protect. The message from this leaked attribute is clear: your site’s overall commitment to user experience is being measured, and the weakest links can harm the whole chain.

A Unified Theory of Clutter – Connecting clutterScore to Q* and Navboost

The evidence from Google’s public statements, the rater guidelines, the DOJ trial, and the Content Warehouse leak does not represent four separate stories. Four parts of a single, coherent narrative explain how Google algorithmically manages the impact of on-page advertising.

Exploring these sources allows us to construct a unified model of how a technical attribute like clutterScore integrates with the major ranking systems we now know are central to Google’s process.

The model rests on the interplay between a “leading indicator” and a “lagging indicator” of poor user experience.

- The leading indicator is

clutterScore. This score can be calculated algorithmically based on a static analysis of a page’s rendered Document Object Model (DOM). The system can identify the number, size, and intrusiveness of ad units, the presence of auto-playing media, the quantity of third-party ad scripts, and other elements defined internally as “distracting/annoying resources”. This calculation can happen during or immediately after rendering, before a critical mass of user interaction data has been collected. It is a proactive measure that predicts a page is likely to provide a poor user experience. - The lagging indicator is the set of user interaction metrics collected by

Navboost. Signals likegoodClicks,badClicks, andlastLongestClicksare the measured effect of the user experience. They are a reactive measure, reflecting what has already happened after real users have engaged with a page. A system that relies solely onNavboostmust wait for users to have a bad experience before it can demote a page.

A truly efficient and scalable quality system would use both. The clutterScore allows Google to be proactive. A page with a high clutterScore can be flagged and have a negative ranking modifier applied pre-emptively. This doesn’t mean Navboost data is ignored; rather, the bar for success is raised. A page flagged for high clutter might need to generate exceptionally positive click signals to overcome the initial penalty and prove to the system that, despite its layout, it is genuinely satisfying users.

This proactive penalty, derived from clutterScore, would then logically feed into the broader, site-level quality assessments. A persistent pattern of high-clutter pages across a domain would contribute to a poor site-wide clutterScore. This negative signal, combined with the inevitably poor Navboost metrics that such pages would generate, would almost certainly serve as a negative input into the calculation of the site’s foundational Q (Quality Score)*. A low Q* acts as a gatekeeper, limiting the ranking potential of all pages on the domain, regardless of their individual relevance.

The following table summarises this unified view, connecting the evidence from each source into a cohesive framework.

This unified model explains how Google can maintain search quality at the scale of billions of pages.

It doesn’t need to wait for every cluttered page to frustrate real users. It can use the leading indicator of clutterScore to identify and suppress probable low-quality experiences, using the lagging indicator of Navboost data to confirm its predictions and refine its models over time.

Strategic Imperatives – Balancing Monetisation and Rank in 2025 and Beyond

The shift from inference to evidence demands a corresponding shift in our strategic approach to on-page monetisation. The existence of a site-level clutterScore and its clear connections to foundational ranking systems like Navboost and Q* means that ad strategy and SEO strategy can no longer operate in separate silos.

They are inextricably linked, and optimising one at the expense of the other is a direct and measurable risk.

The following imperatives should guide any publisher or SEO seeking to balance commercial needs with long-term organic visibility.

Embrace Page Experience as a Core Ranking Pillar

If you’ve ever seen the message “Your site has no URLs with a good page experience” in Google Search Console, you’ve encountered the public face of these quality systems.

This isn’t just a suggestion; it’s a direct signal that your site is failing a fundamental quality check. In 2020, Google’s Sowmya Subramanian announced a pivotal shift: “We will introduce a new signal that combines Core Web Vitals with our existing signals for page experience to provide a holistic picture of the quality of a user’s experience on a web page.”

This was reinforced by Google engineer Philip Walton, who described Web Vitals as “an initiative by Google to provide unified guidance for quality signals that are essential to delivering a great user experience on the web.” SEOs and developers must now focus on these core metrics:

- Largest Contentful Paint (LCP): Measures loading performance. To provide a good user experience, LCP should occur within 2.5 seconds of when the page first starts loading.

- First Input Delay (FID): Measures interactivity. For a good user experience, pages should have an FID of 100 milliseconds or less.

- Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS): Measures visual stability. To provide a good user experience, pages should maintain a CLS of 0.1. or less.

These are not arbitrary benchmarks. They are measurable proxies for user frustration. A page cluttered with slow-loading ad scripts will have a poor LCP. A page where ads pop in and shift content around will have a high CLS.

As John Mueller stated in 2021, “You’ll start to see positive effects once you get out of the “poor” area in core web vitals.” Improving these metrics is not just a technical task; it is fundamentally an exercise in reducing clutter.

Conduct a Comprehensive “Clutter Audit”

The old “above the fold” check is no longer sufficient. A modern audit must be based on the likely components of the clutterScore signal, focusing on any “distracting/annoying resources”. This requires a deep analysis of the rendered DOM of a representative sample of pages across the entire site, including:

- Intrusive Elements: Identify all interstitials, welcome mats, sticky footers, and pop-ups, particularly those that violate mobile interstitial policies.

- Media Elements: Catalogue all auto-playing video or audio players, especially those that play with sound enabled by default.

- Ad Density and Layout: Go beyond a simple count. Analyse the total screen real estate consumed by ads, especially in the initial viewport. Pay close attention to ad units that cause significant layout shifts as they load.

- Script and Resource Load: Scrutinise the number and performance of third-party scripts, particularly those from ad networks and programmatic exchanges. These are often a primary source of page slowdowns and instability, contributing to a poor user experience.

Model the Financial Trade-Off

The existence of a site-level penalty for clutter creates a clear financial trade-off that must be modelled. An aggressive ad unit might generate £X in direct monthly revenue, but if it contributes to a higher clutterScore that suppresses sitewide rankings by Y%, the resulting loss in organic traffic value could be far greater than £X. Publishers must move towards a model of rigorous testing.

Systematically remove or replace specific ad units and measure the impact not only on direct ad revenue but also on key SEO metrics like rankings, organic traffic, and conversions over a statistically significant period.

This data is essential for making informed decisions about which monetisation strategies are truly profitable in the long run.

Enforce Site-Level Consistency

Because clutterScore is a site-level signal; a clutter audit cannot be limited to a site’s top 10 or 20 landing pages.

The entire domain is being evaluated. This means a comprehensive strategy must be developed for older, legacy content that may have been monetised aggressively in the past. Publishers must make difficult decisions about these sections: are they worth the effort to de-clutter and bring into line with modern user experience standards?

Or do they represent a significant enough risk to the site’s overall quality score that they should be noindexed, consolidated, or removed entirely? A policy of benign neglect is no longer a safe option.

Conclusion: From Speculation to Evidence

With Google giving specific advice on Ads, pop-ups and interstitials (especially on mobile versions of your site), you would be wise to be careful about employing a pop-up window that obscures the primary reason for visiting any page on your site.

QUOTE “Showing a popup that covers the main content, either immediately after the user navigates to a page from the search results, or while they are looking through the page.” Google, 2016

If Google detects any user dissatisfaction, this can be very bad news for your rankings.

QUOTE: “Interstitials that hide a significant amount of content provide a bad search experience” Google, 2015

Consider, instead, using an exit pop-up window as hopefully by the time a user sees this device, they are FIRST satisfied with the page content they came to read.

It is sensible to convert customers without using techniques that potentially negatively impact Google rankings.

We have moved from speculation to evidence.

The combination of sworn testimony from the DOJ v. Google trial and the technical blueprint provided by the Content Warehouse API leak confirms what many in the professional SEO community have long suspected. On-page clutter, driven by aggressive monetisation, is not a soft, subjective “user experience” factor. It is a hard, quantifiable, site-level technical signal named clutterScore.

This signal does not exist in isolation. We can now draw a clear, evidence-based line from the distracting ads on a page to the low Page Quality score assigned by a human rater, to the negative training data fed into Google’s machine learning systems, to the calculation of a punitive clutterScore, and finally, to the negative impact on the user satisfaction data measured by Navboost and the foundational authority assessed by the site-wide Q* score.

The internal conflict at Google between its ad business and its search product is now public knowledge, and the algorithms that penalise clutter are the Search team’s most potent defence. For publishers and SEOs, ignoring this reality is no longer a viable strategy.

It is a direct and measurable risk to a site’s authority, its visibility, and its long-term success in Google Search. The evidence is in, and the verdict is clear: in the perpetual balancing act between monetisation and rank, clutter carries a cost.

The question for business owners now evidently is “How do I balance making money from my site with maintaining my Google rankings?”.

Disclosure: Hobo Web uses generative AI when specifically writing about our own experiences, ideas, stories, concepts, tools, tool documentation or research. Our tool of choice for this process is Google Gemini Pro 2.5 Deep Research. This assistance helps ensure our customers have clarity on everything we are involved with and what we stand for. It also ensures that when customers use Google Search to ask a question about Hobo Web software, the answer is always available to them, and it is as accurate and up-to-date as possible. All content was verified as correct by the author at time of publishing. See our AI policy.

References

Thank you to these references:

- The Google Content Warehouse API Leak 2024 – Hobo SEO Auditor

- Closing Deck: Search Advertising: U.S. and Plaintiff States v. Google LLC

- An Anonymous Source Shared Thousands of Leaked Google Search API Documents with Me; Everyone in SEO Should See Them – SparkToro

- Mobile-first Indexing Best Practices | Google Search Central | Documentation

- Search Quality Rater Guidelines: An Overview – Google

- Google Publisher Policies – Google AdSense Help

- Secrets from the Algorithm: Google Search’s Internal Engineering Documentation Has Leaked – iPullRank

- Better ad standards – Think with Google

- No Plans to Speed Core Web Vitals Data Collection- Google’s Mueller – PPCexpo

- U.S. and Plaintiff States v. Google LLC [2020] – Trial Exhibits – Department of Justice

- Women Techmakers Summit – Opening Remarks and Diversity At Google featuring Sowmya Subramanian

- The Initial Better Ads Standards

- Plaintiffs’ Remedies Opening Statement [Redacted Version]: U.S and Plaintiff States v. Google LLC [2020]