Get a full SEO audit for your website

This is a preview of Chapter 1 from my new ebook – Strategic SEO 2025 – a PDF which is available to download for free here. Published on: 10 July 2025 at 06:07

TL;DR

TL;DR

Google’s DOJ trial disclosures confirm that search ranking hinges on two top-level signals – Quality (Q*) and Popularity (P*) – powered by modular systems like Navboost, Topicality, and PageRank, with user interaction data at the core. SEO success now depends on trust, authority, user engagement, freshness, and adapting to potential legal-driven changes in Google’s architecture.

SEO really can be broken down, based on Google V DOJ evidence, into “Minding your P*s and Q*s”. “Knowing your A, B and Cs”, “dotting your I’s” and “crossing your T*s”.

Key Takeaways: DOJ v. Google – SEO Insights (2025)

-

Two Core Signals Drive Ranking: Google’s system reduces to Quality (Q*) and Popularity (P*), revealed in DOJ trial documents.

-

Modular Architecture: Underlying systems like Topicality (T*), Navboost, and RankBrain feed into those top-level signals.

-

User Data Is Central: Clicks, scrolls, Chrome visit data, dwell time, and pogo-sticking are leveraged as critical ranking feedback.

-

Hand-Crafted Signals Dominate: Most ranking factors are engineered manually, not black-box ML, for control and stability.

-

Freshness Matters: Google boosts recency for queries where timeliness is essential (news, events), balancing against historical clicks.

-

Links Still Core: PageRank (distance from trusted sources), anchor text, and backlink quality remain crucial authority signals.

-

Context Layers Refine Results: Location and personalisation heavily shape what individual users see beyond the “universal” rank.

-

AI as Final Layer: RankBrain, BERT, and MUM don’t replace hand-crafted signals — they refine them with semantic understanding.

-

⚖️ Legal Impact Ahead: DOJ remedies may force changes to Google’s ranking systems, shaping SEO strategy going forward.

United States et al. v. Google LLC

The antitrust case, United States et al. v. Google LLC, initiated by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2020, represents the most significant legal challenge to Google’s market power in a generation.

While the legal arguments focused on market monopolisation, the proceedings inadvertently became a crucible for technical disclosure, forcing Google to all but reveal the long-guarded secrets of its search engine architecture.

The trial’s technical revelations were not incidental; they were central to the core legal conflict.

The DOJ’s case rested on the premise that Google unlawfully maintained its monopoly in general search and search advertising through a web of anticompetitive and exclusionary agreements with device manufacturers and browser developers, including Apple, Samsung, and Mozilla.

These contracts, often involving payments of billions of dollars annually, ensured Google was the pre-set, default search engine for the vast majority of users, thereby foreclosing competition by denying rivals the scale and data necessary to build a viable alternative.

This legal challenge created a strategic paradox for Google.

To counter the DOJ’s accusation that its dominance was the result of illegal exclusionary contracts, Google’s primary defence was to argue that its success is a product of superior quality and continuous innovation – that users and partners choose Google because it is simply the best search engine available.

This “superior product” defence, however, could not be asserted in a vacuum.

To substantiate the claim, Google was compelled to present evidence of this superiority, which necessitated putting its top engineers and executives on the witness stand. Individuals like Pandu Nayak, Google’s Vice President of Search, and Elizabeth Reid, Google’s Head of Search, were tasked with explaining, under oath, the very systems that produce this acclaimed quality.

Consequently, the act of defending its market position legally forced Google to compromise its most valuable intellectual property and its long-held strategic secrecy.

The sworn testimonies and internal documents entered as evidence provided an unprecedented, canonical blueprint of Google’s key competitive advantages.

At the heart of these revelations is the central role of user interaction data.

A recurring theme throughout the testimony was that Google’s “magic” is not merely a static algorithm but a dynamic, learning system engaged in a “two-way dialogue” with its users.

Every click, every scroll, and every subsequent query is a signal that might teach the system what users find valuable.

This continuous feedback loop, operating at a scale that Google’s monopoly ensures no competitor can replicate, is the foundational resource for the powerful ranking systems detailed in the trial.

The Architecture of Google Search Ranking

The trial testimony and exhibits dismantle the popular conception of Google’s ranking system as a single, monolithic algorithm. Instead, they reveal a sophisticated, multi-stage pipeline composed of distinct, modular systems, each with a specific function and data source. This architecture is built upon a foundation of traditional information retrieval principles and human-engineered logic, which is then powerfully refined by systems that leverage user behaviour data at an immense scale.

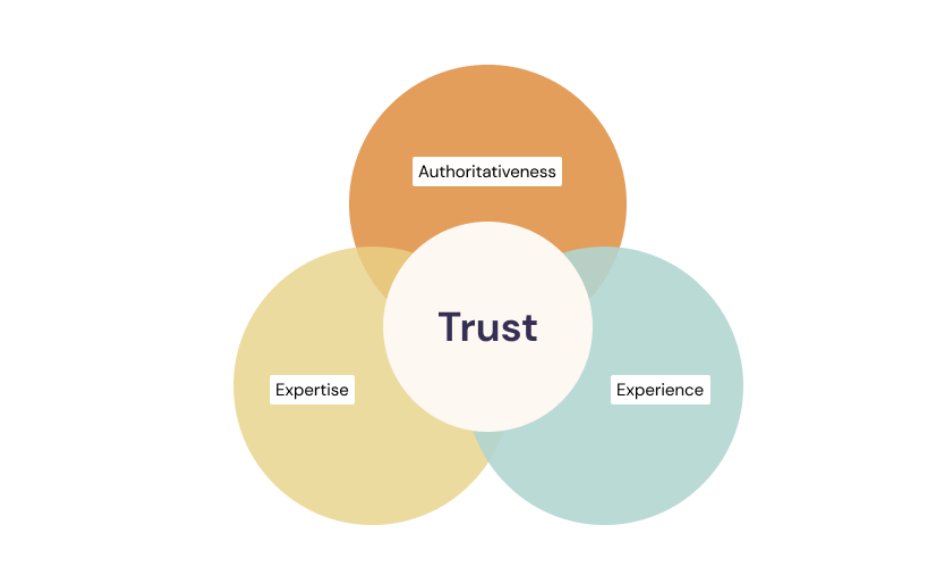

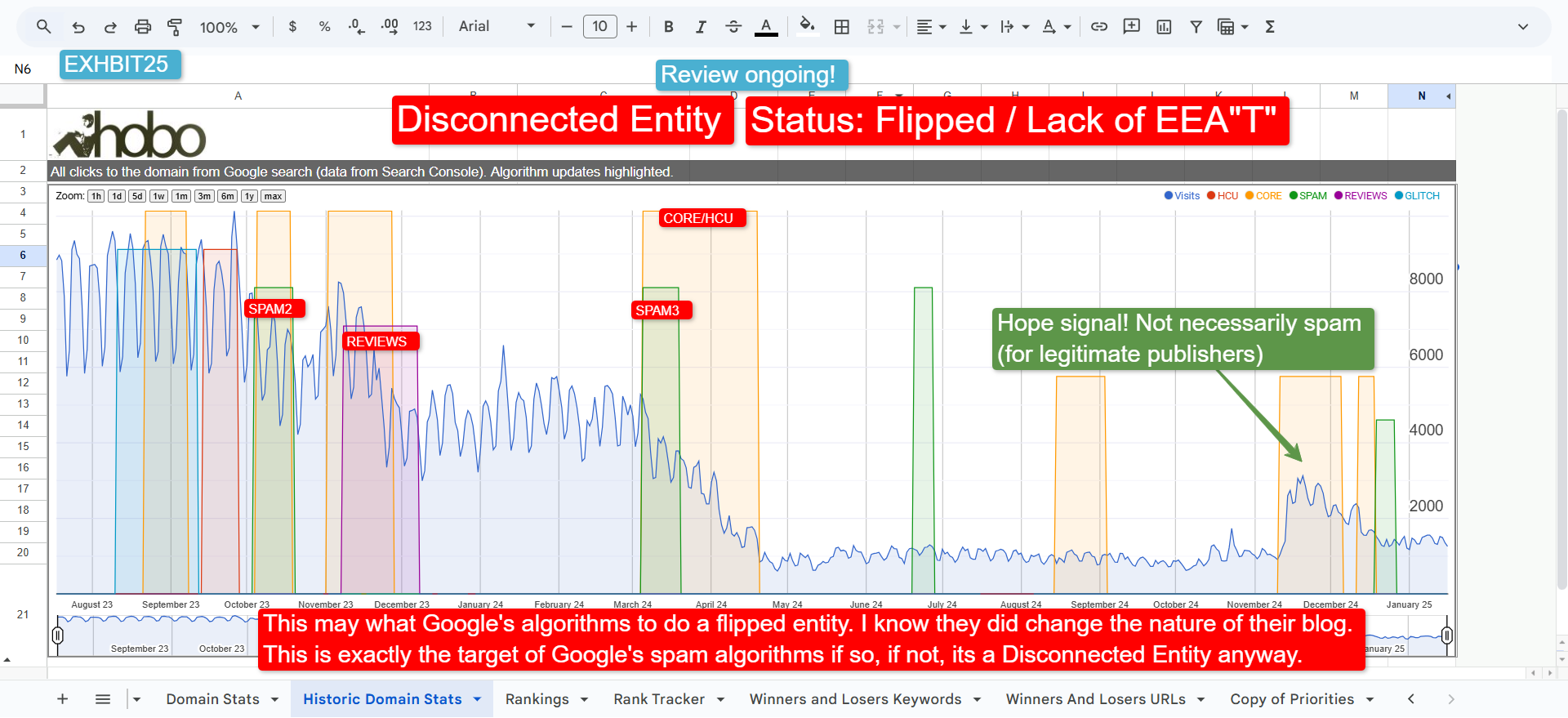

While initial trial exhibits hinted at this modularity, the later unredacted remedial opinion in the DOJ v. Google case provided the definitive, high-level blueprint. The court revealed that Google has two “fundamental top-level ranking signals” that are the primary inputs for a webpage’s final score: Quality (Q*) and Popularity (P*). These two signals also help Google determine how frequently to crawl webpages to keep its index fresh.

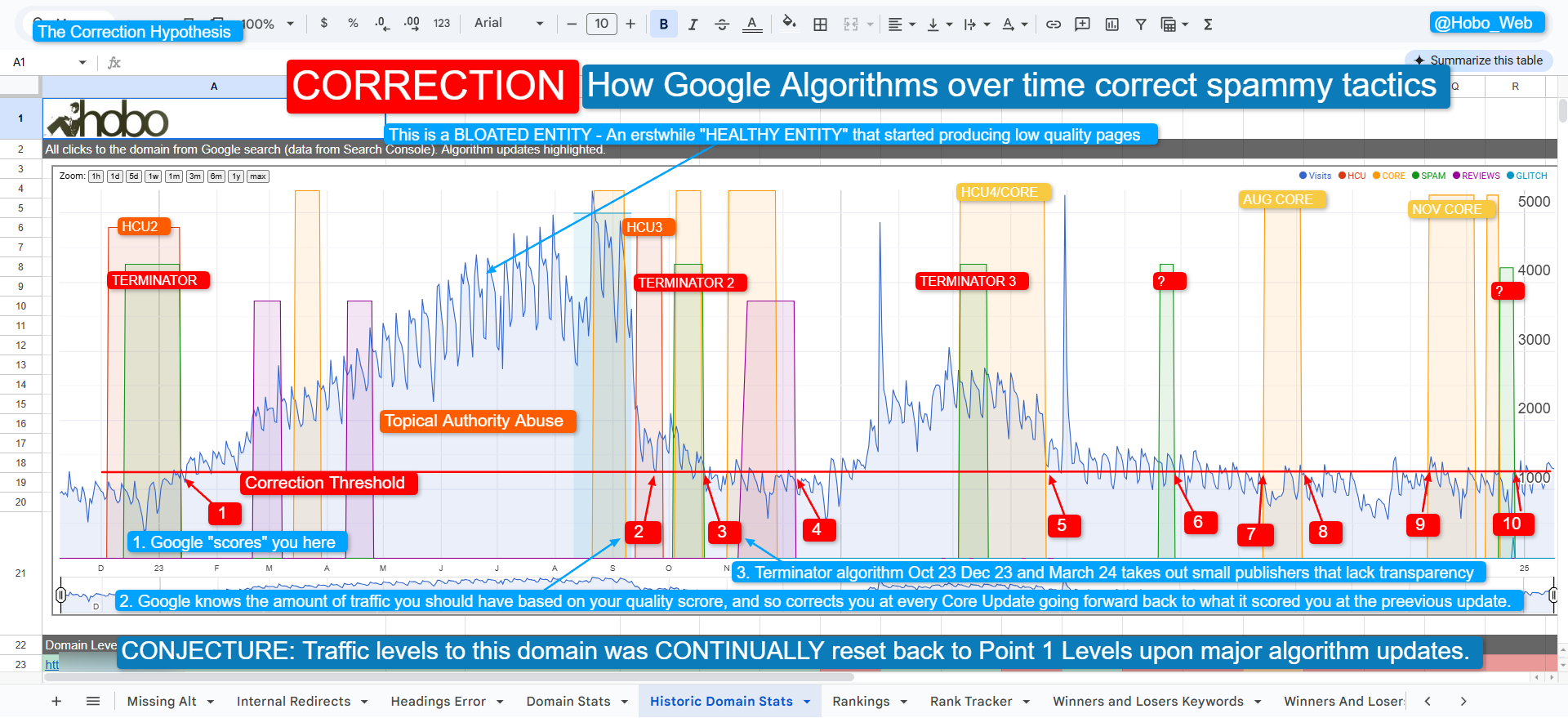

This analysis details the core components of this architecture, showing how the previously revealed systems of Topicality (T*), Navboost, and Q* are the essential building blocks for Google’s top-level signals.

The Two Pillars of Ranking: An Overview

The following table summarises the confirmed two-pillar architecture. The systems detailed in the original trial are now best understood as the underlying components that feed into these two fundamental signals.

Deconstructing the Signals: The Core Systems

The foundational systems revealed during the trial provide the mechanics for the top-level signals.

Quality Score (Q*) – The Engine of the ‘Quality’ Signal

The Quality Score (Q*) is the internal system that assesses the overall trustworthiness and quality of a website or domain. It is a hand-crafted, largely static score that functions as the core of the top-level Quality signal. Its key data inputs include PageRank and the link distance from trusted “seed” sites, which align perfectly with the remedial opinion’s description of the Quality signal.

Navboost and Topicality (T*) – The Engines of the ‘Popularity’ Signal

The top-level Popularity (P*) signal is powered by a combination of systems that measure user engagement and link structures.

- Navboost: This is the primary user interaction engine. As revealed in Pandu Nayak’s testimony, Navboost is a data-driven system that refines rankings based on 13 months of aggregated user click data, including metrics like good, bad, and “last longest” clicks. This system draws its information from a vast, underlying data warehouse codenamed ‘Glue’, which logs the trillions of user interactions that Google processes. The explicit confirmation of Chrome visit data as a direct input for the Popularity signal was particularly significant, as Google had historically been less direct about the extent to which it leverages its browser’s data for ranking purposes. It provides the “Chrome visit data” and “user interaction” components of the P* signal.

- Topicality (T*): This system computes a document’s direct relevance to query terms and serves as a foundational score. Testimony from engineer HJ Kim revealed it is composed of “ABC” signals:

- Anchors (A), Body (B), and Clicks (C). Within the new framework:

- The Anchors (A) and Clicks (C) components serve as direct inputs to the Popularity (P*) signal.

- The Body (B) component, based on the text of the document itself, is a “content-derived metric” that feeds into the Quality signal.

- Anchors (A), Body (B), and Clicks (C). Within the new framework:

Information Retrieval and the Primacy of “Hand-Crafted” Signals

Contrary to the prevailing narrative of an all-encompassing artificial intelligence, the trial revealed that Google’s search ranking systems are fundamentally grounded in signals that are “hand-crafted” by its engineers.

This deliberate engineering philosophy prioritises control, transparency, and the ability to diagnose and fix problems, a stark contrast to the opaque, “black box” nature of more complex, end-to-end machine learning models.

The deposition of Google Engineer HJ Kim was particularly illuminating on this point. He testified that “the vast majority of signals are hand-crafted,” explaining that the primary reason for this approach is so that “if anything breaks, Google knows what to fix“.

This methodology is seen as a significant competitive advantage over rivals like Microsoft’s Bing, which was described as using more complex and harder-to-debug ML techniques.

The process of “hand-crafting” involves engineers analysing relevant data, such as webpage content, user clicks, and feedback from human quality raters, and then applying mathematical functions, like regressions, to define the “curves” and “thresholds” that determine how a signal should respond to different inputs.

This human-in-the-loop system ensures that engineers can modify a signal’s behaviour to handle edge cases or respond to public challenges, such as the spread of misinformation on a sensitive topic.

This foundational layer of human-engineered logic provides the stability and predictability upon which more dynamic systems are built.

Trustworthiness

“Q* (page quality (i.e., the notion of trustworthiness)) is incredibly important. If competitors see the logs, then they have a notion of “authority” for a given site.” February 18, 2025, Call with Google Engineer HJ Kim (DOJ Case)

I agree – if this information were made available, it would be abused.

The emergence of these distinct systems – T* for query-specific relevance, Q* for static site quality, and Navboost for dynamic user-behaviour refinement – paints a clear picture of a modular, multi-stage ranking pipeline.

The process does not rely on a single, all-powerful algorithm.

Instead, it appears to be a logical sequence: initial document retrieval is followed by foundational scoring based on relevance (T*) and trust (Q*).

This scored list is then subjected to a massive re-ranking and filtering process by Navboost, which leverages the collective historical behaviour of users.

Only the small, refined set of results that survives this process is passed to the final, most computationally intensive machine learning models.

This architecture elegantly balances the need for speed, scale, and accuracy, using less expensive systems to do the initial heavy lifting before applying the most powerful models.

Freshness (Timeliness of Content)

Google also considers freshness – how recent or up-to-date the information on a page is, especially for queries where timeliness matters.

Trial testimony and exhibits detailed how freshness influences rankings:

- Freshness as a Relevance Signal: “Freshness is another signal that is ‘important as a notion of relevance’,” Pandu Nayak testified regmedia.co.uk. In queries seeking current information, newer content can be more relevant. Nayak gave an example: if you’re searching for the latest sports scores or today’s news, “you want the pages that were published maybe this morning or yesterday, not the ones that were published a year ago.” regmedia.co.uk Even if an older page might have been relevant in general, it won’t satisfy a user looking for the latest updates. Thus, Google’s ranking system will favour more recently published pages for fresh information queries. Conversely, for topics where age isn’t detrimental (say, a timeless recipe or a classic novel), an older authoritative page can still rank well. As Nayak put it, “deciding whether to use [freshness] or not is a crucial element” of delivering quality results regmedia.co.uk – Google must judge when recency should boost a result’s ranking and when it’s less important.

- Real-Time Updates for Breaking Queries: John Giannandrea (former head of Google Search) explained that “Freshness is about latency, not quantity.” It’s not just showing more new pages, but showing new information fast when it’s needed regmedia.co.uk. “Part of the challenge of freshness,” he testified, “is making sure that whatever gets surfaced to the top… is consistent with what people right now are interested in.” regmedia.co.uk For example, “if somebody famous dies, you kind of need to know that within seconds,” Giannandrea said regmedia.co.uk. Google built systems to handle such spikes in information demand. An internal 2021 Google document (presented in court) described a system called “Instant Glue” that feeds very fresh user-interaction data into rankings in near real-time. “One important aspect of freshness is ensuring that our ranking signals reflect the current state of the world,” the document stated. “Instant Glue is a real-time pipeline aggregating the same fractions of user-interaction signals as [the main] Glue, but only from the last 24 hours of logs, with a latency of ~10 minutes.” justice.gov In practice, this means if there’s a sudden surge of interest in a new topic (e.g. breaking news), Google’s algorithms can respond within minutes by elevating fresh results (including news articles, recent forum posts, etc.) that match the new intent. Google also uses techniques (code-named “Tetris” in one exhibit) to demote stale content for queries that deserve fresh results and to promote newsy content (e.g. Top Stories) when appropriate justice.gov

- Balancing Freshness vs. Click History: One difficulty discussed at trial is that older pages naturally accumulate more clicks over time, which could bias ranking algorithms that learn from engagement data. Nayak noted that pages with a long history tend to have higher raw click counts than brand-new pages (simply by having been around longer) regmedia.co.uk. If the system naively preferred results with the most clicks, it might favour an outdated page that users have clicked on for years, over a fresher page that hasn’t had time to garner clicks. “Clicks tend to create staleness,” as one exhibit put it regmedia.co.uk. To address this, Google “compensates” by boosting fresh content for queries where recency matters, ensuring the top results aren’t just the most popular historically, but the most relevant now. In essence, Google’s ranking algorithms include special freshness adjustments so that new, pertinent information can outrank older but formerly popular pages when appropriate regmedia.co.uk. This keeps search results timely for the user’s context.

Linking Behaviour (Link Signals and Page Reputation)

The trial also illuminated how Google uses the web’s linking behaviour – how pages link to each other – as a core ranking factor. Links serve both as votes of authority and as contextual relevance clues:

- Backlink Count & Page Reputation: Google evaluates the number and quality of links pointing to a page to gauge its prominence. Dr. Lehman explained during testimony that a ranking “signal might be how many links on the web are there that point to this web page or what is our estimate of the sort of authoritativeness of this page.”regmedia.co.uk In other words, Google’s algorithms look at the link graph of the web to estimate a page’s authority: if dozens of sites (especially reputable ones) link to Page X, that’s a strong indication that Page X is important or trustworthy on its topic. This principle underlies PageRank and other authority signals. By assessing “how many links… point to the page,” Google infers the page’s popularity and credibility within the web ecosystem regmedia.co.uk. (However, it’s not just raw counts – the quality of linking sites matters, as captured by PageRank’s “distance from a known good source” metric justice.gov.)

- Anchor Text (Link Context): Links don’t only confer authority; they also carry information. The anchor text (the clickable words of a hyperlink) tells Google what the linked page is about. As noted earlier, Pandu Nayak highlighted that anchor text provides a “valuable clue” to relevance regmedia.co.uk. For example, if dozens of sites hyperlink the text “best wireless headphones” to a particular review page, Google’s system learns that the page is likely about wireless headphones and is considered “best” by those sources, boosting its topical relevancy for that query. This context from linking behaviour helps Google align pages to queries beyond what the page’s own text says. It’s a way of leveraging the collective judgment of website creators: what phrases do others use to describe or reference your page? Those phrases become an external signal of the page’s content. Google combines this with on-page signals (as part of topicality scoring) to better understand a page’s subject matter regmedia.co.uk.

- Link Quality over Quantity: Not all links are equal. Through PageRank and related “authority” algorithms, Google gives more weight to links from reputable or established sites. One trial exhibit described PageRank as measuring a page’s proximity to trusted sites (a page linked by high-quality sites gains authority; one linked only by dubious sites gains much less) justice.gov. This shows that linking behaviour is evaluated qualitatively. A single backlink from, say, a respected news outlet or university might boost a page’s authority more than 100 backlinks from low-quality blogs. Google also works to ignore or devalue spammy linking schemes. (While specific anti-spam tactics weren’t detailed in the trial excerpts we saw, the focus on “authoritative, reputable sources” implies that links from spam networks or “content farms” are discounted – aligning with Google’s long-standing efforts to prevent link manipulation.) I go into link building more in my article on Link building for beginners.

In summary, the DOJ’s antitrust trial pulled back the curtain on Google’s ranking system.

Topicality signals (page content and context from anchors) tell Google what a page is about and how relevant it is to a query.

Authority signals (like PageRank and quality scores) gauge if the page comes from a trustworthy, reputable source.

Freshness metrics ensure the information is up-to-date when timeliness matters. And the web’s linking behaviour – both the number of links and the anchor text – feeds into both relevance and authority calculations.

All these factors, largely handcrafted and fine-tuned by Google’s engineers justice.gov, work in concert to rank the billions of pages on the web for any given search.

As Pandu Nayak summed up in court, Google uses “several hundred signals” that “work together to give [Google Search] the experience that is search today.” regmedia.co.uk

Each factor – topical relevance, authority, freshness, links, and many more – plays a part in Google’s complex, evolving ranking algorithm, with the aim of delivering the most relevant and reliable results to users.

The Final Layers: Location and Personalisation

While the core systems produce a universal ranking based on quality and popularity, the results a user actually sees are heavily tailored by a final, powerful layer of context. The trial focused on the foundational architecture, but the live search experience is profoundly shaped by signals specific to the individual user.

- Location as a Dominant Signal: For a vast number of queries, the user’s physical location is the single most important ranking factor. For searches like “pubs near me” or “solicitors in Greenock,” Google’s core algorithm is secondary to its ability to identify relevant, local results. It determines a user’s location with high precision using device GPS, Wi-Fi signals, and IP addresses to transform a generic query into a geographically specific and immediately useful answer.

- Personalisation from Search History: Beyond location, Google refines rankings based on a user’s individual search history. This system learns a user’s interests and intent over time to resolve ambiguity. For instance, a user who frequently searches for software development topics will likely see results about the programming language if they search for “python,” whereas a user whose history is filled with zoology queries will see results about the snake. This layer of personalisation ensures that the final search results page is not just a list of high-quality, popular documents, but a bespoke answer sheet tailored to the user’s implicit context and previous behaviour.

Beyond RankBrain: The Shift to Semantic Understanding

The trial rightly highlighted RankBrain as a pioneering use of machine learning in search. However, to understand Google’s modern capabilities, it is crucial to recognise that its AI has since evolved from simply interpreting novel queries to fundamentally understanding the meaning of language itself. This represents a shift towards semantic search.

Subsequent models like BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) changed the game entirely. Unlike earlier systems that processed words in a query one by one, BERT analyses the full context of a word by looking at the words that come before and after it. This is critical for understanding nuance and intent. For example, in the query “can you get medicine for someone pharmacy,” BERT understands that the preposition “for” is the most important word, fundamentally changing the query’s meaning.

This evolution continued with later models like MUM (Multitask Unified Model), designed to understand information across different languages and formats (like images and text) simultaneously. These advanced AI systems do not replace the foundational signals like Navboost or Q*. Instead, they act as a supremely intelligent final analysis layer. They take the pool of high-quality, relevant results identified by the core systems and re-rank them based on a deep, contextual comprehension of what the user truly means, making the search engine feel less like a database and more like a dialogue.

A Forward-Looking Note on Legal Remedies

Looking ahead, it is important to note that while this architecture represents Google’s current competitive advantage, the ongoing remedies phase of the DOJ trial could mandate changes to these very systems. The future of search, therefore, may be shaped as much by court rulings as by Google’s own engineers.

SEO Evidence Brief

DOJ v. Google – Case No. 20-cv-3010 (Remedial Phase Opinion)

Full source: Court PDF

1. User Data as a Core Input

“User data is a critical input that directly improves [search] quality. Google utilizes user data at every stage of the search process, from crawling and indexing to retrieval and ranking.”

View in PDF

2. Learning from User Feedback

“Learning from this user feedback is perhaps the central way that web ranking has improved for 15 years.”

View in PDF

3. Page Scoring in Crawling

“Google assigns a score to the pages it crawls, and it endeavors to exclude from its web search index pages without value to users, such as spam-heavy or pornographic pages. Google also relies on various ‘ranking signals’… Among Google’s top-level signals are those measuring a web page’s quality and popularity.”

View in PDF

4. Quality & Popularity Signals in Crawling

“Quality and popularity signals, for instance, help Google determine how frequently to crawl web pages to ensure the index contains the freshest web content.”

View in PDF

5. PageRank as an Input to Quality Score

“PageRank… is a single signal relating to distance from a known good source, and it is used as an input to the Quality score.”

View in PDF

6. Source of Quality Signals

“Most of Google’s quality signal is derived from the webpage itself.”

View in PDF

7. Human Raters as Training Data for RankEmbed

“The data underlying RankEmbed models is a combination of click-and-query data and scoring of web pages by human raters.”

View in PDF

8. Direct Role of Rater Scores

“RankEmbed and its later iteration RankEmbedBERT are ranking models that rely on two main sources of data: % of 70 days of search logs plus scores generated by human raters…”

View in PDF

9. Rater Data Improves Long-Tail Search

“RankEmbedBERT was again one of those very strong impact things, and it particularly helped with long-tail queries where language understanding is that much more important.”

View in PDF

10. Raw vs. Deep-Learning Ranking Signals

“Google uses signals to score and rank web pages… Signals range in complexity. There are ‘raw’ signals, like the number of clicks, the content of a web page, and the terms within a query… At the other end… innovative deep-learning models… like RankEmbedBERT.”

View in PDF

Source: Pages 141–142gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

11. Spam Score as a Quality Signal

“So, too, does the spam score… Query data is also important to ensuring that the search index contains the pages that are responsive to users’ queries.”

View in PDF

Source: Page 142gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

12. User Queries as Training Data

“Every [user] interaction gives us another example, another bit of training data: for this query, a human believed that result would be most relevant.”

View in PDF

Source: Page 95gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

13. Signals from Device & Context

“One of the signals that does go into Google Search is: is it a desktop query or is it a mobile query.”

View in PDF

Source: Page 94gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

14. Chrome Visit Data as a Popularity Signal

“Popularity is based on Chrome visit data and the number of anchors… used to promote well-linked documents.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 147gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

15. Freshness & Long-Tail Queries

“Comprehensiveness of the index is crucial… Freshness, or the recency of information, is an important factor in search quality. GSEs need to know how to recrawl sites… especially for long-tail queries.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 96gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

16. Scale, Quality, and User Trust

“The quality of the experience drives retention — users lose trust in a search engine when they’re not given accurate and relevant information.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 98gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

17. Glue & Navboost Data (Super Query Logs)

“Glue is essentially a ‘super query log’… The data underlying Glue consists of… (1) the query (text, language, location, device type); (2) ranking info (10 blue links, triggered search features); (3) SERP interactions (clicks, hovers, dwell time); (4) query interpretation (spelling correction, salient terms). An important component of the Glue data is Navboost… a ‘memorization system’ that aggregates click-and-query data.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Pages 155–157gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

18. RankEmbed Training Data = Quality Edge

“The RankEmbed data is a ‘small fraction’ of Google’s overall traffic, but the RankEmbed models trained on that data have directly contributed to the company’s quality edge over competitors.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 162gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

19. User-Side Data Defined (Click & Query Logs)

“User-side Data is data Google collects from the pairing of a user query and the returned response… Examples include: links clicked, hover time, pogo-sticking (click back), and dwell time. User-interaction data is the raw material Google uses to improve search services.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 155gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

20. Quality Measures & PageRank as Authoritativeness

“A key quality signal is PageRank, which captures a web page’s quality and authoritativeness based on the frequency and importance of the links connecting to it… and is used as an input to the Quality score.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 146gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

21. Spam Scores & Device-Type Flags in Indexing

“The spam score will allow rivals to avoid crawling web pages of low value and focus only on those with helpful content. Finally, the device-type flag will enable competitors to close the mobile scale gap by identifying and focusing on mobile-friendly websites.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 148gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

22. User Interaction Signals (Clicks, Hovers, Pogo-Sticking, Dwell Time)

“Examples of such data include the web link or vertical information the user clicks on, how long a user hovers over a link, and whether the user clicks back from a web page and how quickly… User-interaction data is the raw material that Google uses to improve search services.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 156gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

23. Required Disclosure of Quality, Popularity, Spam & Device-Type Flags

“For each DocID, a set of signals, attributes, or metadata… including (A) popularity as measured by user intent and feedback systems including Navboost/Glue, (B) quality measures including authoritativeness, (C) spam score, (D) device-type flag…”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 140gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

24. Spam & Low-Value Pages Excluded from Index

“Google assigns a score to the pages it crawls, and it endeavors to exclude from its web search index pages without value to users, such as spam-heavy or pornographic pages.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 145gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

25. Filtering Training Data for Quality (Duplicates, Spam, Garbage)

“It is a common business practice to filter your models… remove duplicates, remove spam, garbage, inappropriate content. There’s a lot of stuff out there that you don’t want to put into your models.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 34gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

26. Index Size & the “80–20 Problem”

“The size of Google’s index gives it a key competitive advantage… Building a search index that can answer 80% of queries is attainable, but answering the remaining 20% — the long-tail queries — is particularly challenging.”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 143gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

27. Popularity Signal from Chrome Visit Data

“*Popularity signal (P) ‘uses Chrome data’… a measure quantifying the number of links between pages and used to promote well-linked documents.**”

View in PDF with highlight

Source: Page 147gov.uscourts.dcd.223205.1436.0_4

Download your free ebook.

This article is an excerpt from my SEO book – Strategic SEO 2025.

Disclosure: Hobo Web uses generative AI when specifically writing about our own experiences, ideas, stories, concepts, tools, tool documentation or research. Our tools of choice for this process is Google Gemini Pro 2.5 Deep Research and ChatGPT 5. This assistance helps ensure our customers have clarity on everything we are involved with and what we stand for. It also ensures that when customers use Google Search to ask a question about Hobo Web software, the answer is always available to them, and it is as accurate and up-to-date as possible. All content was verified as correct by Shaun Anderson. See our AI policy.